Another medical article, this one a review of the Mutter Museum’s Civil War exhibit. For those with strong stomachs, it looks like a fascinating visit.

The new exhibition focuses in part on Philadelphia’s role in the Civil War. It was not a battleground, but about 157,000 injured soldiers were transported here by train or steamboat for treatment. Though civilian clinics admitted some, a number of military hospitals were also built, including two that were almost cities unto themselves, each with more than 3,000 beds.

On display are surgical instruments like a hammer and chisel, knives and saws used for amputations and an unnervingly long pair of “ball forceps” for extracting bullets. Most of these grisly operations were done with the soldiers knocked out by chloroform or ether, the curators note — contrary to the common belief that there was no anesthesia back then and only a bullet to bite on.

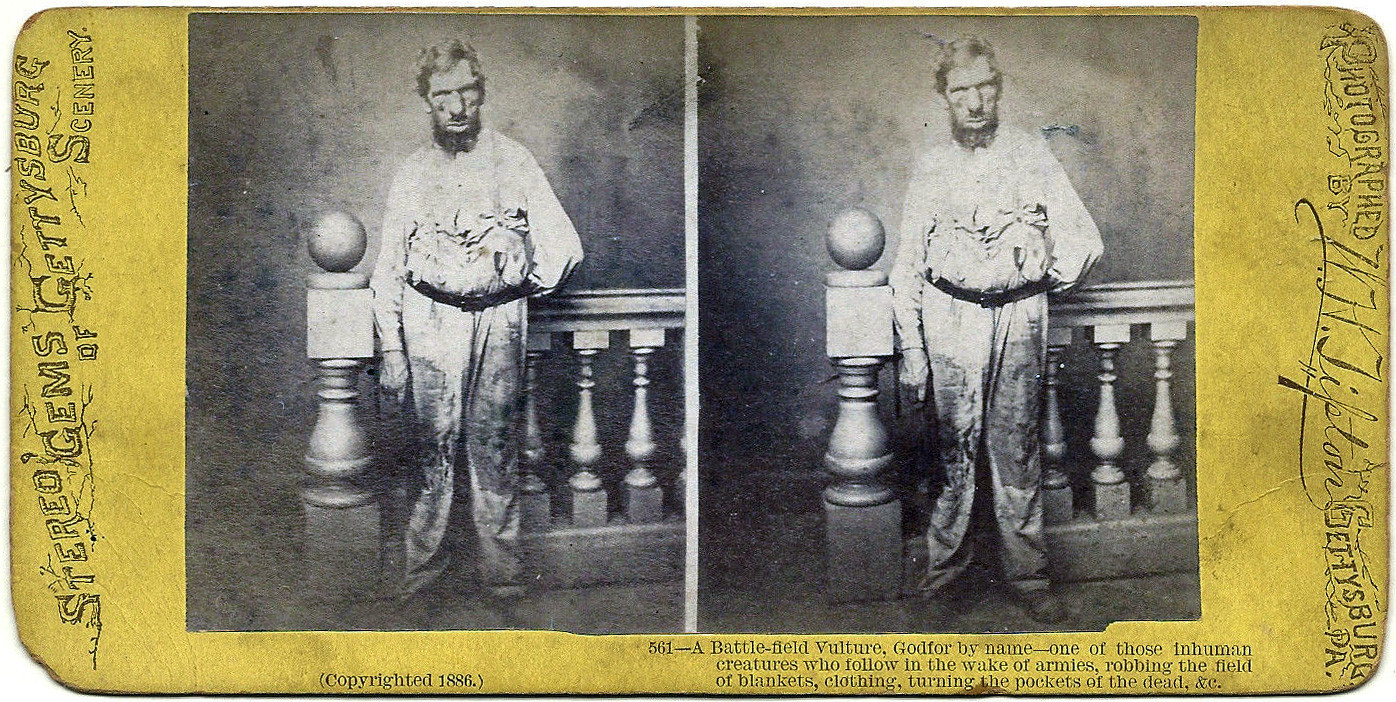

One display case holds the broken skull of a soldier who was shot through both eye sockets. Stark photographs reveal young men with limbs missing, faces mutilated, and piercing, haunted eyes. Others, still able-bodied, are shown burying the fallen.

via ‘Broken Bodies, Suffering Spirits’ at the Mütter Museum – NYTimes.com.