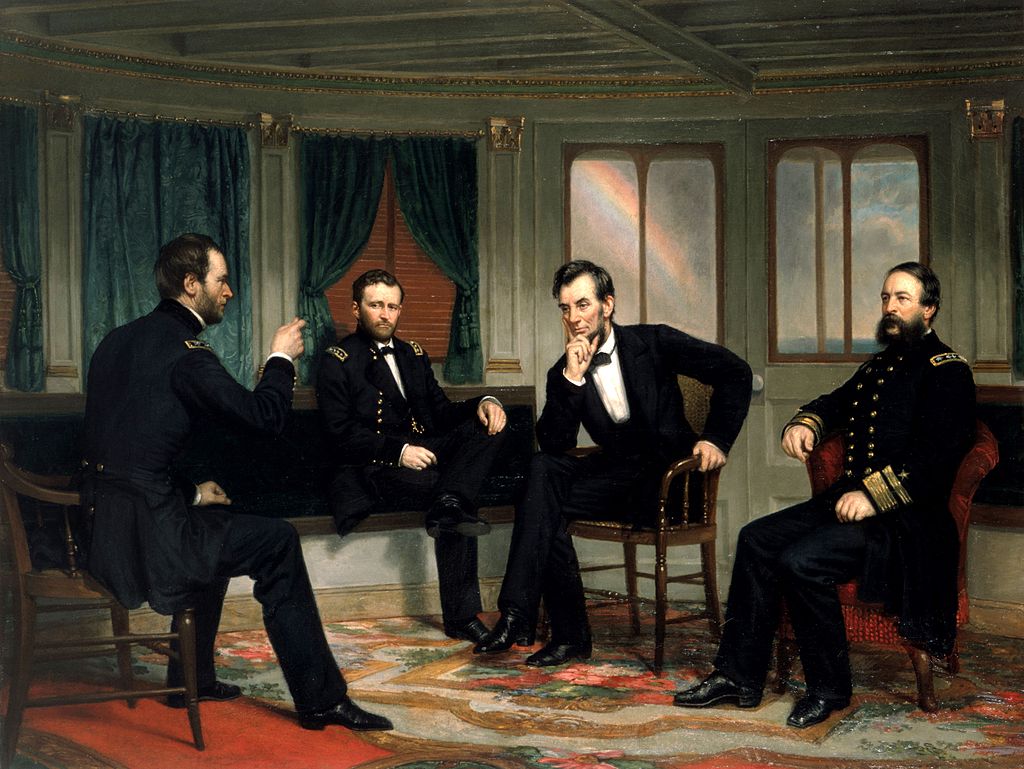

In yesterday’s post on Bunny Breckinridge, I mentioned his great-grandpa’s fury at Sherman’s whiskey-based neglect. It’s a great story, and I’ve copy-pasted a version here. It’s taken from the memoirs of John S. Wise, son of the Virginia governor Henry A. Wise. Through him Wise Jr. had apparently told him by Joe Johnston – the other General in the room during the negotiations.

“Well, nearly everything to drink had been absorbed. For several days, Breckinridge had found it difficult, if not impossible, to procure liquor. He showed the effect of his enforced abstinence. He was rather dull and heavy that morning. Somebody in Danville had given him a plug of very fine chewing tobacco, and he chewed vigorously while we were awaiting Sherman’s coming. After a while, the latter arrived. He bustled in with a pair of saddlebags over his arm, and apologized for being late. He placed the saddlebags carefully upon a chair. Introductions followed, and for a while General Sherman made himself exceedingly agreeable. Finally, some one suggested that we had better take up the matter in hand.

“Yes,” said Sherman, “but, gentlemen, it occurred to me that perhaps you were not overstocked with liquor, and I procured some medical stores on my way over. Will you join me before we begin work ?

General Johnston said he watched the expression of Breckinridge at this announcement, and it was beatific. Tossing his quid into the fire, he rinsed his mouth, and when the bottle and the glass were passed to him, he poured out a tremendous drink, which he swallowed with great satisfaction. With an air of content, he stroked his mustache and took a fresh chew of tobacco.

Then they settled down to business, and Breckinridge never shone more brilliantly than he did in the discussions which followed. He seemed to have at his tongue’s

end every rule and maxim of international and constitutional law, and of the laws of war, international wars, civil wars, and wars of rebellion. In fact, he was so resourceful, cogent, persuasive, learned, that, at one stage of the proceedings, General Sherman, when confronted by the authority, but not convinced by the eloquence or learning of Breckinridge, pushed back his chair and exclaimed: “See here, gentlemen, who is doing this surrendering anyhow? If this thing goes on, you ll have me sending a letter of apology to Jeff Davis.”

Afterward, when they were Hearing the close of the conference, Sherman sat for some time absorbed in deep thought. Then he arose, went to the saddlebags, and fumbled for the bottle. Breckinridge saw the movement. Again he took his quid from his mouth and tossed it into the fireplace. His eye brightened, and he gave every evidence of intense interest in what Sherman seemed about to do.

The latter, preoccupied, perhaps unconscious of his action, poured out some liquor, shoved the bottle back into the saddle-pocket, walked to the window, and stood there, looking out abstractedly, while he sipped his grog.

From pleasant hope and expectation the expression on Breckinridge s face changed successively to uncertainty, disgust, and deep depression. At last his hand sought the plug of tobacco, and, with an injured, sorrowful look, he cut off another chew. Upon this he ruminated during the remainder of the interview, taking little part in what was said.

After silent reflections at the window, General Sherman bustled back, gathered up his papers, and said: “These terms are too generous, but I must hurry away before you make me sign a capitulation. I will submit them to the authorities at Washington, and let you hear how they are received.” With that he bade the assembled officers adieu, took his saddlebags upon his arm, and went off as he had come.

General Johnston took occasion, as they left the house and were drawing on their gloves, to ask General Breckinridge how he had been impressed by Sherman.

“Sherman is a bright man, and a man of great force,” replied Breckinridge, speaking with deliberation, “but,” raising his voice and with a look of great intensity, ” General Johnston, General Sherman is a hog. Yes, sir, a hog. Did you see him take that drink by himself?”

General Johnston tried to assure General Breckinridge that General Sherman was a royal good fellow, but the most absent-minded man in the world. He told him that the failure to offer him a drink was the highest compliment that could have been paid to the masterly arguments with which he had pressed the Union commander to that state of abstraction.

“Ah!” protested the big Kentuckian, half sighing, half grieving, ” no Kentucky gentleman would ever have taken away that bottle. He knew we needed it, and needed it badly.”